Charles Hatfield: The Rainmaker

Lost History

As conversations and accusations around chemtrails and sky-spraying grow more prevalent, I wanted to take a moment to explore the story of the original chemical rainmaker, Charles Hatfield.

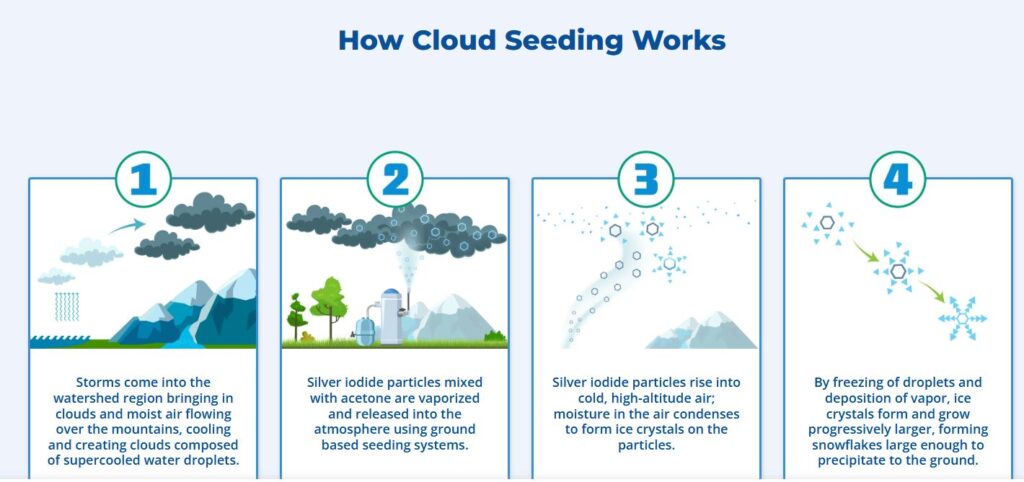

Before we go deep, I do want to touch base on the state’s current cloud-seeding project by sourcing the Santa Ana Watershed Project Authorities breakdown on exactly how cloud-seeding works. I will show below an illustrations from their website breaking down how cloud seeing currently works:

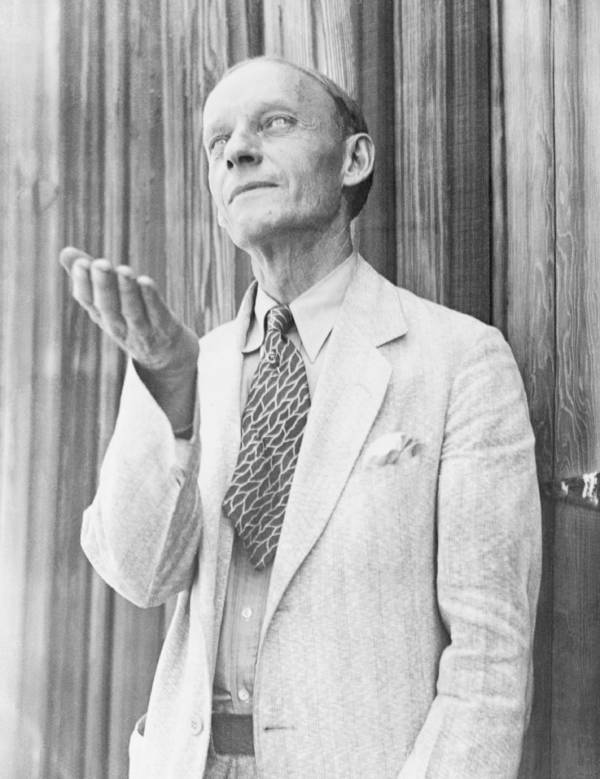

About Charles Hatfield

It sounds like something straight out of a movie and in a sense it is: a man who could make it rain by mixing and burning various chemicals into the air. His recipe was top-secret, only known by him and he took it to the grave. This man was named Charles Hatfield and his story of being a rainmaker has many ties to some of San Diego’s crazier history.

The year was 1915 and as the story often goes, San Diego was in a horrible drought. At the time, the city was growing and the newly constructed dam at Lake Morena was yet to be filled even a third of the way. Otay lake and other reservoirs in the city were having similar issues.

The year was 1915 and as the story often goes, San Diego was in a horrible drought. At the time, the city was growing and the newly constructed dam at Lake Morena was yet to be filled even a third of the way. Otay lake and other reservoirs in the city were having similar issues.

Word had circulated about Hatfield, a folk legend at the time, who claimed to have made it rain more than 500 times around the world.

Rainmakers were a thing during this period, but most were thought of as scammers. As with any profession, there will be those who are authentic and those who are just trying to make a quick buck. Hatfield seems to have been an authentic one.

There is some evidence linking back to ancient times that certain chemical combinations could make it rain. For instance, it was rumored that massive amounts of dead bodies emitted fumes that could create rainfall.

During the Vietnam war, Operation Popeye was an operation used to induce rain and extend the East Asian Monsoon season in support of U.S. government efforts related to the War in Southeast Asia. A report titled Rainmaking in SEASIA shows that the military used a combination of lead iodide and silver iodide released by aircraft.

This program was developed in California at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake and tested in Okinawa, Guam, Philippines, Texas, and Florida in a hurricane study program called Project Stormfury. The operation’s goal was to increase rainfall in carefully selected areas to deny the Vietnamese enemy, namely military supply trucks, the use of roads by:

So clearly, rainmaking is not only used by scam artists. The city of San Diego was desperate during this lengthy drought and as quirky as it may have sounded, they hired Hatfield. They offered him $10,000 which would be granted after fulfilling his promises to make it rain. A formal agreement was never drawn up, though Hatfield continued his job based off of verbal understanding.

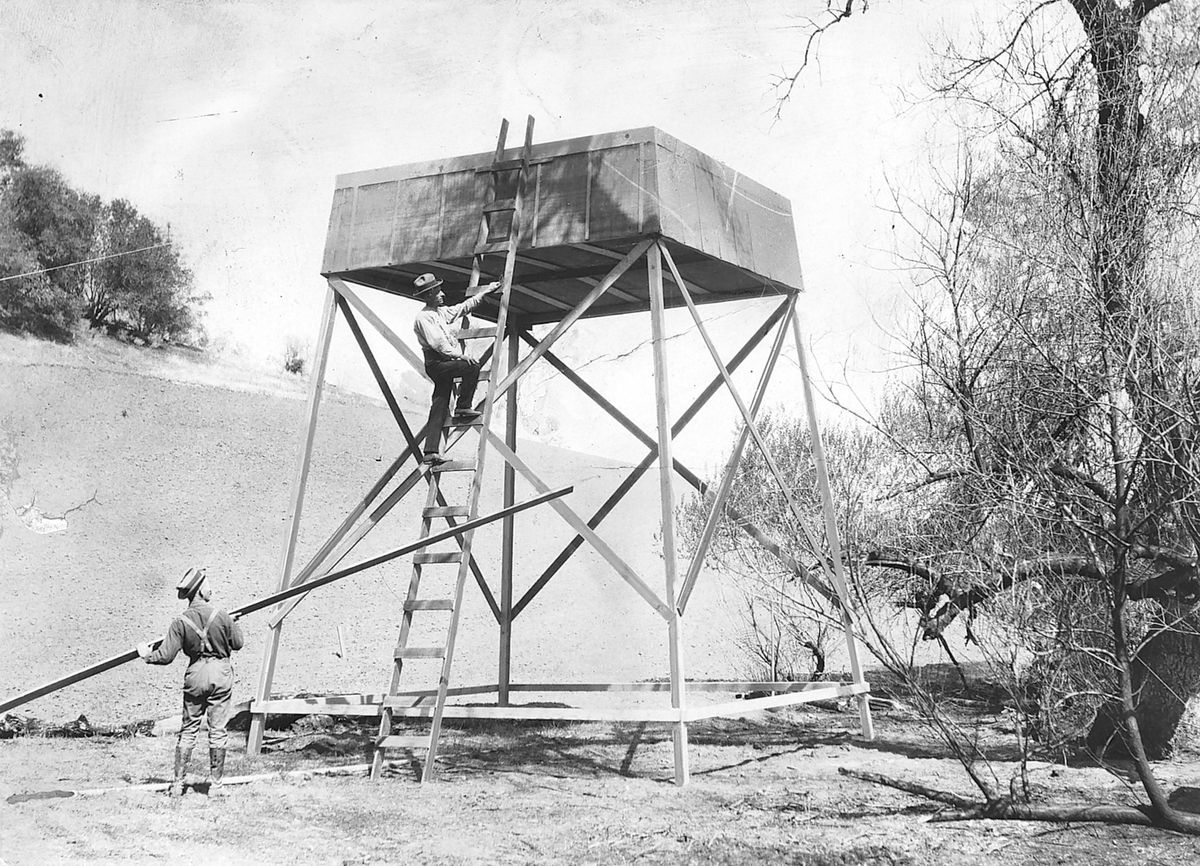

On January 1, 1916, Charles and his brother set up their rainmaking tower beside the Morena Reservoir and got to work. Throughout the upcoming days, Hatfield would mix and release a combination of chemicals into the air. Four days later the rain began. Then, it wouldn’t stop. For the next two weeks rain poured down heavily on the city with few breaks in between.

Dry creekbeds turned into raging rivers and floods began destroying everything in sight. Homes were submerged, people and animals killed and the Sweetwater and Savage dams overflowed. As the rain continued to rage through the city, the Savage dam eventually broke, increasing the death toll to 20 people at that point.

Hatfield viewed this all as a success, but when he went to collect his $10,000 he was met with outrage and threats. People were literally looking to lynch him. Hatfield claimed that the damage was not his fault and that the city should have taken the necessary precautions beforehand.

The city refused to pay him his money, citing that there were already claims worth $3.5 million. Hatfield attempted to settle for $4,000 but eventually had to take the city to court. In two trials, the rain was ruled an act of God but Hatfield continued the suit until 1938. At this point, two courts decided that the rain was still an act of God, which removed him from any wrongdoing, but also meant he did not get his fee. It is impossible at this point to say exactly how many people died but it is estimated to be somewhere between 20-60 people.

A shot of the Lake Morena dam:

And a shot of Savage Dam at Lower Otay Lake, which ended up bursting and killing villagers who lived below:

Several films and books have been written which were inspired by Hatfield including the 1956 Burt Lancaster film: The Rainmaker. Hollywood even invited Hatfield to the premiere. A southern jam band called ‘Widespread Panic’ wrote a song called Hatfield which is a tribute song to his life and the band ‘Steppin’ in It’ wrote a song called Weatherman.

There are a few places in San Diego to check out if you are interested in tying together the small pieces from this catastrophic event:

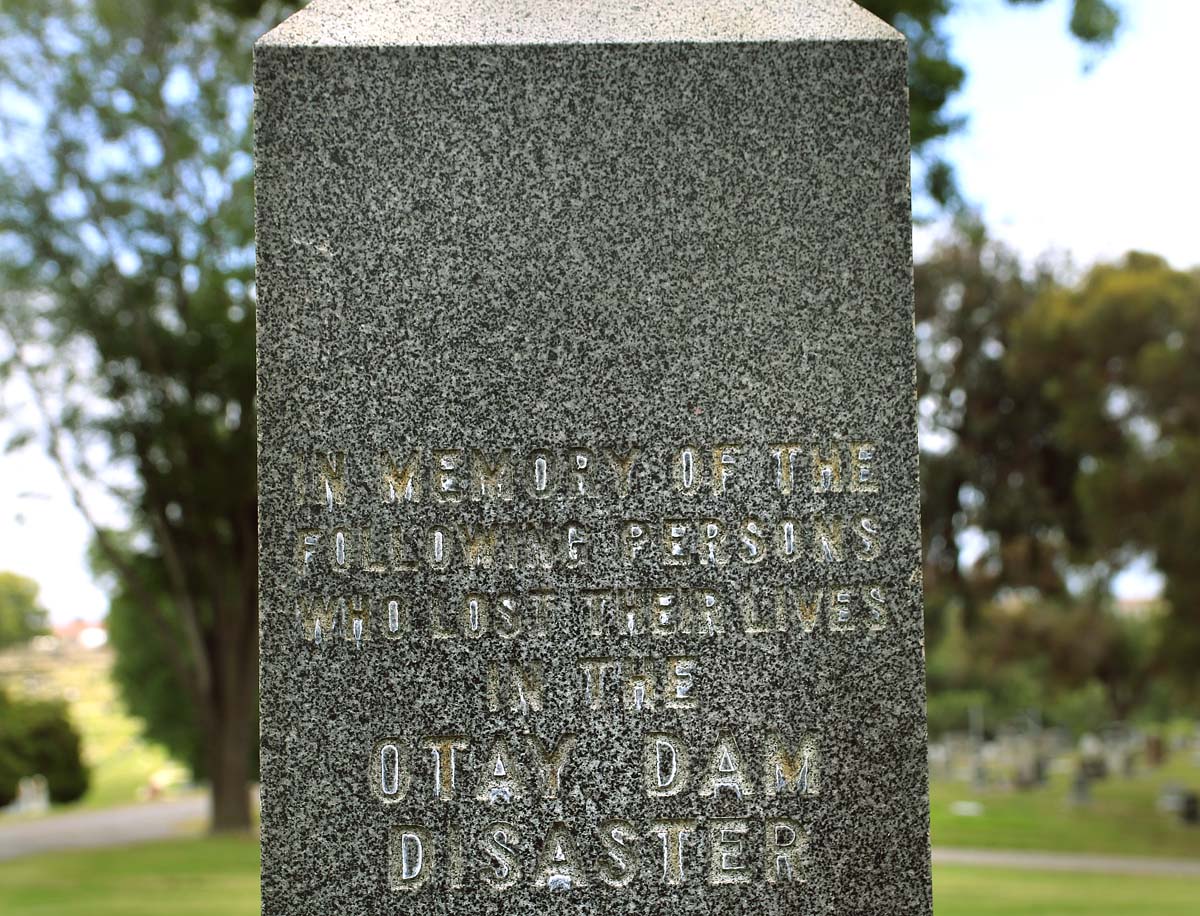

Many of the people that died in the flood were Japanese farmers and lived in the valleys. In the following days after the flood, Japanese people could be seen in South Bay searching for deceased or missing loved ones by boat. A memorial for these victims can be viewed at Mount Hope Cemetery. The obelisk reads “In memory of the following persons who lost their lives in the Otay Dam Disaster”.

A plaque can be found at Lake Morena campground for Charles Hatfield and his hand in the great flood:

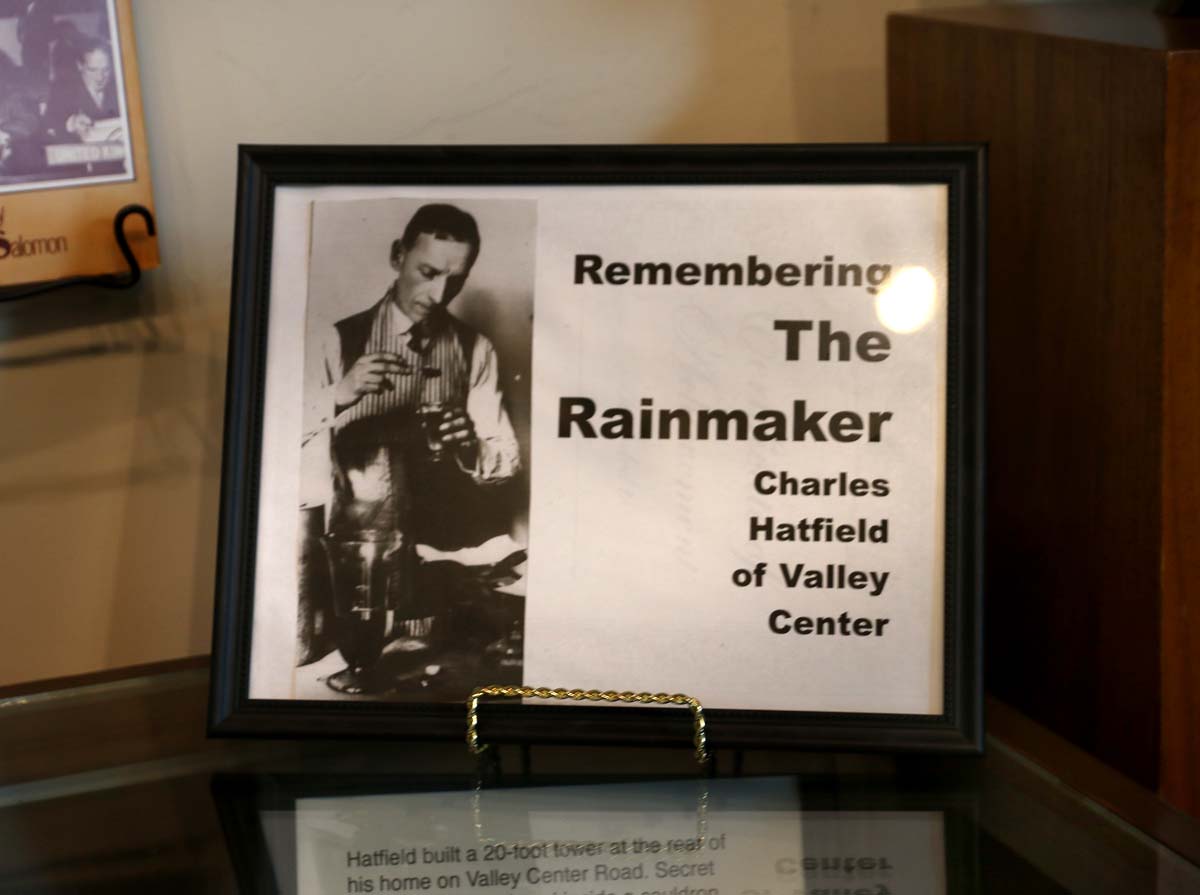

The Valley Center Historical Society also had a nice spread on Mr. Hatfield. It is said that he lived in Valley Center at some point in his life. The alleged home was still standing until 2013, when it was finally purchased by developers and demolished:

Here is a great, informative documentary on Hatfield and his life growing up in San Diego and his cloud-seeding practice: