Farewell Jack Murphy Stadium

Article by David Johnson:

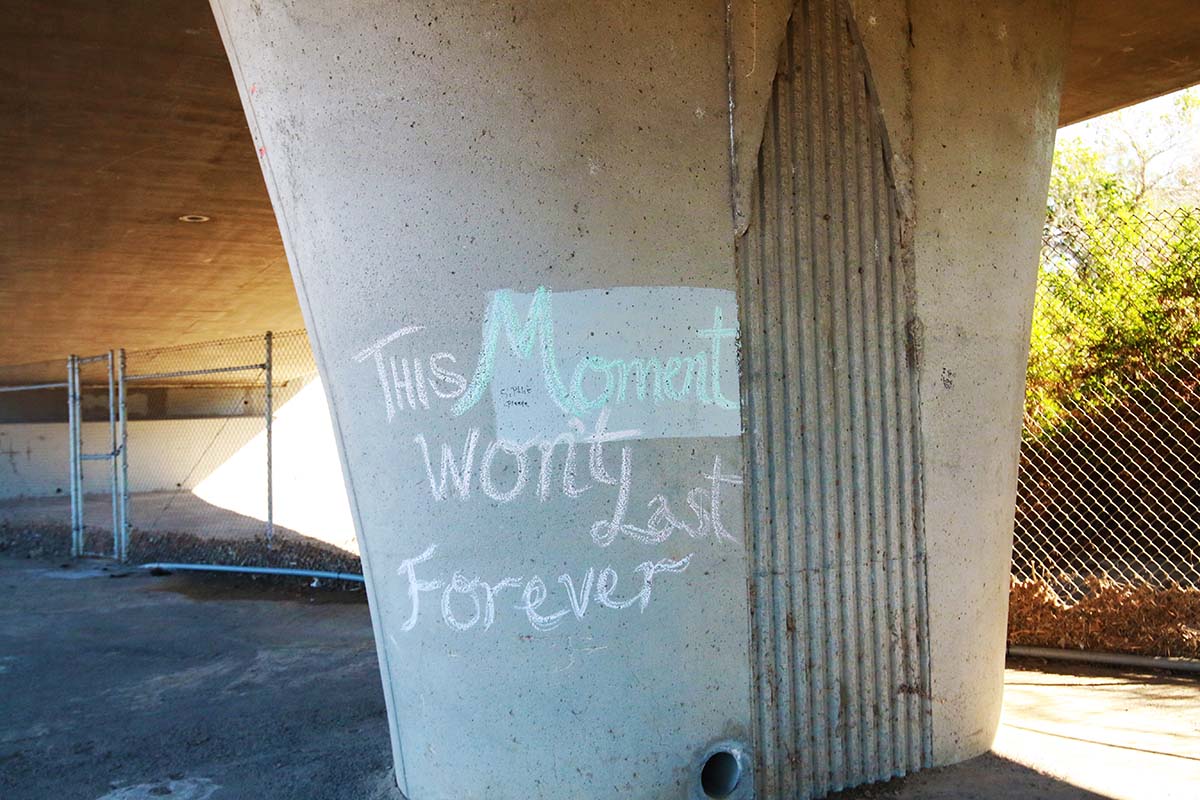

As this is being written in January of 2021, San Diego Stadium is being torn down in Mission Valley. In its infancy, it was a tangible symbol of San Diego’s evolution from a sleepy border town to an elite world-class city. But the fact that we could neither maintain it properly nor replace it with something intended to keep San Diego in the major leagues of cities is evidence that we have some great problems.

The intensity of your ties to the stadium that is disappearing before our eyes probably depends on your age and your favorite activities. If you are of Medicare age, the stadium went up and came down in your lifetime. If you are very much younger, you don’t remember a Mission Valley without it.

The intensity of your ties to the stadium that is disappearing before our eyes probably depends on your age and your favorite activities. If you are of Medicare age, the stadium went up and came down in your lifetime. If you are very much younger, you don’t remember a Mission Valley without it.

When I arrived in San Diego at the age of ten in late 1958, San Diego had one foot in its past and one in its future. It was a magical place to a small-town boy, full of attractions like beaches, the San Diego Zoo, Belmont Park and the El Cortez Hotel with its outside glass elevator. Within a couple more years, the College Grove and Mission Valley shopping centers opened and greatly expanded shopping options for San Diegans.

Back then San Diego had a population of 550,000 and ranked as about the twentieth largest city in the United States. But in many ways, it was still in the minor leagues. San Diego State was not yet a university and its sports teams played in what is now Division II of the NCAA. Its football team played in Aztec Bowl (capacity 12,500) and its basketball team played in an on-campus gymnasium that predated the now seemingly ancient Peterson Gym. The Padres were a AAA minor league team just moving into brand new Westgate Park in Mission Valley. There was no professional football team and no stadium capable of supporting it in the unlikely case one desired to come here.

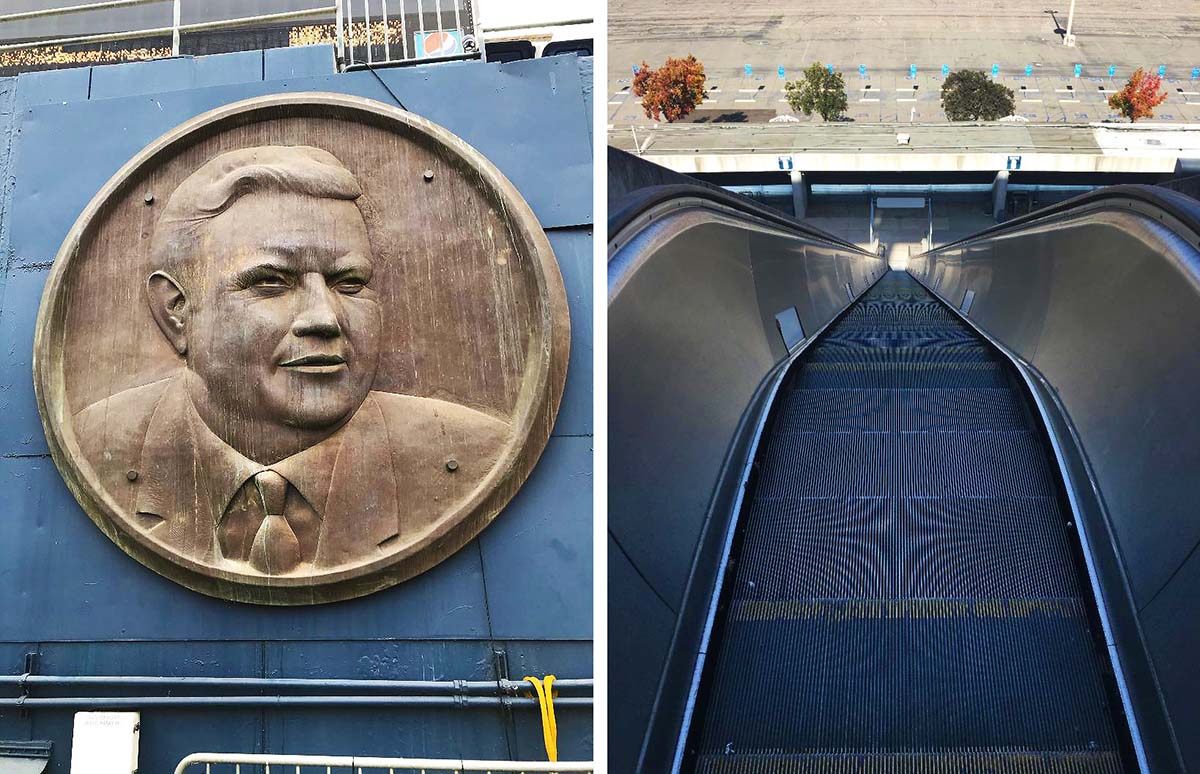

But the city was on the way up, and sports were to play a big role. The American Football League was born in a Chicago hotel in the summer of 1959, and a local sportswriter named Jack Murphy saw a future for them in San Diego. In late 1960 he began to beat the drums for making San Diego the home of the then and now Los Angeles Chargers.

When those efforts reached fruition a year later, he turned his attention to getting a major league baseball expansion team for San Diego. Westgate Park held only 8,300 fans and while its design included expansion capability, it soon became clear that a large multipurpose stadium would serve all needs.

When those efforts reached fruition a year later, he turned his attention to getting a major league baseball expansion team for San Diego. Westgate Park held only 8,300 fans and while its design included expansion capability, it soon became clear that a large multipurpose stadium would serve all needs.

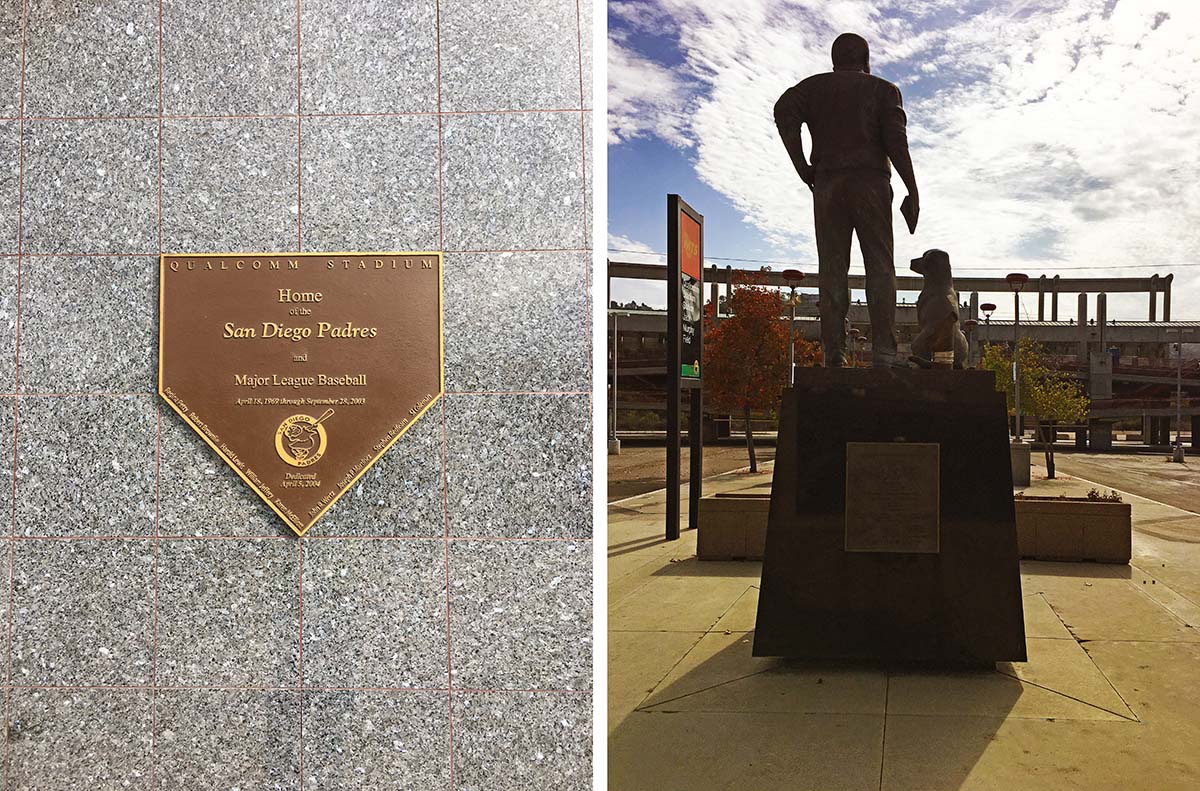

In 1965 voters approved a $27 million bond issue to build a stadium on the site of the last remaining Mission Valley dairy, and construction began a month later. The first game played at the stadium was a Charger’s pre-season game in August of 1967, and they had a record of 8-5-1 in their first season there. The AAA Padres played there in 1968, compiling a record of 76-70, and the expansion National League Padres began play in in 1969.

While the presence of a large and modern stadium ushered in a whole new era of sports and entertainment in San Diego, it was a house of continual heartache and pain for sports fans. The early Padres were inept and borderline unwatchable. Total attendance for the first five years at San Diego Stadium was less than the three million fans that attended during the Padres’ first year in Petco Park in 2003.

Plagued by poor attendance, the team was about to be moved to Washington D.C. in 1974 when McDonald’s magnate Ray Kroc stepped in and bought the team to keep it here. Even with active ownership, the Padres managed to be about the worst team in baseball in their 35 years in the stadium. They won exactly one World Series game in that time. By contrast, the Yankees won 31 World Series games over that stretch and the Florida Marlins (who didn’t even exist until 1993) won eight.

Plagued by poor attendance, the team was about to be moved to Washington D.C. in 1974 when McDonald’s magnate Ray Kroc stepped in and bought the team to keep it here. Even with active ownership, the Padres managed to be about the worst team in baseball in their 35 years in the stadium. They won exactly one World Series game in that time. By contrast, the Yankees won 31 World Series games over that stretch and the Florida Marlins (who didn’t even exist until 1993) won eight.

The Chargers were also historically inept. In fifty-five years in San Diego, they compiled a net losing record and went to one Super Bowl. Their one league championship was during the pre-NFL 1962-63 season when they slaughtered the Boston Patriots 51-10. At that point the future looked bright for the Chargers but looks were deceiving.

They were wildly entertaining during the Dan Fouts-Air Coryell era, and went to their only Super Bowl during the Stan Humphries-Bobby Ross years but mostly they stunk. I personally had the misfortune to be a paying customer at the “Holy Roller” game where the hated Raiders fumbled the ball through multiple offensive player hands into the end zone where tight end Dave Casper recovered it for a game winning touchdown. Forward fumble recoveries by offenses are now illegal in the NFL, but that didn’t assuage the pain of Charger fans. The superior success of the Raiders and Denver Broncos was frustrating and undermined citizen support for the team.

The misery engendered by San Diego sports teams is germane to the fate of the stadium now falling before our eyes. Petco Park construction was approved by a 60% majority of voters in the heady days after the Padres won the second pennant of their long existence in 1998. Many of those voters were not sports fans, but rather foresaw the enhancements to the East Village area that rose up around Petco Park afterwards.

The Chargers had the misfortune (or more to the point gall) to use the threat of moving the team elsewhere to try to blackmail voters into giving the Spanos family a taxpayer funded stadium in the wake of years of losing. Had the twenty-first century Chargers been as entertaining as the Chargers of the early 1960s or 1980s, the outcome may have been different.

The Chargers had the misfortune (or more to the point gall) to use the threat of moving the team elsewhere to try to blackmail voters into giving the Spanos family a taxpayer funded stadium in the wake of years of losing. Had the twenty-first century Chargers been as entertaining as the Chargers of the early 1960s or 1980s, the outcome may have been different.

But the team was exasperating, and in the 21st century, football palaces were the province of billionaire owners who self-funded facility construction. The Spanos family lacked the means and will to live in that financial stratosphere, so the Chargers moved and the stadium was orphaned.

San Diego Stadium was born in a decade (1965-75) when multi-use stadiums were also built in Pittsburgh, Oakland, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Houston and Atlanta. Only the Oakland Coliseum is still in use, and all of the others with the exception of the Houston Astrodome have been demolished. I would expect that single use facilities like Petco Park will have much longer lives. They still play baseball in Wrigley Field in Chicago (opened in 1914) and Fenway Park in Boston (opened 1912).

By the time my kids were born in the 1980s, San Diego was fully entrenched as an elite American city. San Diego State College was now SDSU, and its alumni were in elected and executive positions in business and government all over town. The city was now home to UCSD which, in a quarter century, had been born and become a world class university. San Diego was also a hub of innovation in high tech, bio tech, aero tech and many other emerging centers of commerce.

But there were cracks in San Diego’s infrastructure that included the stadium, and the city lacked the financial wherewithal to keep up. Water mains seemed to blow up weekly, streets went unrepaired for decades, and coping with drought and wildfires became higher priorities for government.

But there were cracks in San Diego’s infrastructure that included the stadium, and the city lacked the financial wherewithal to keep up. Water mains seemed to blow up weekly, streets went unrepaired for decades, and coping with drought and wildfires became higher priorities for government.

Any chance of saving the stadium by modernizing and maintaining it evaporated, but it was not an inevitable loss. Assets can be preserved. The County of San Diego still operates out of a magnificent and well-maintained bay front structure for which ground was broken eighty-five years ago during the Great Depression.

As it goes down, we will remember the Murph as more than a sports stadium. During its 55 years of life, a pantheon of great entertainers appeared there including the Rolling Stones, the Who, Guns N’ Roses, Pink Floyd, the Eagles, Billy Joel, Elton John, Bob Dylan, U2, Beyoncé and the Beach Boys among others. It was also used for supercross, monster truck events, a Billy Graham crusade and as an evacuation center during two recent wildfires.

There are still among us San Diegans who saw the AAA Padres play at Lane Field on the bay, or who watched professional basketball in the San Diego Concourse, but their numbers are diminishing. Someday people who attended events at “The Murph” will tell their grandchildren about the magnificent concrete structure which once stood at the center of San Diego life.