Influencer: Antonio Garra

Article by: David Johnson

This page is part of our “Influencers” section, where I will tell the stories of historic figures of the past as well as present day people who are positively influencing our city. I plan on doing a deep-comb of every person featured and really learning who they are or were. I will also include places we can still visit today that they either helped create or plaques in memory of them.

On the afternoon of January 19, 1852, Cupeño tribal chief Antonio Garra was marched with his hands bound to a newly dug grave in the local San Diego Catholic cemetery. He was accompanied by a Catholic priest who, as they walked, invited him to pray for his soul. Garra repeatedly declined and observers noted that Garra appeared to know more Latin than the priest. Kneeling in front of his freshly dug grave, Garra was was repeatedly urged by his captors to offer some last words of remorse for his deeds. In answer Garra finally said, “Gentlemen, I ask your pardon for all of my offenses, and accept yours in return.” Seconds later, he was executed by a squad of twelve riflemen.

Not a lot is known about Antonio Garra’s early life, but much can be assumed by the circumstances among San Diego County Native Americans in the first half of the 19th century. Doubt has been cast about his tribal affiliation at birth with some claiming he was of Quechan or alternatively Yuma origins. In any case we know he was born around the turn of the 19th century and was brought at a young age to the San Luis Rey Mission in present day Oceanside. He was reported to be fluent in five native languages in addition to English, Spanish and Latin.

San Luis Rey Mission where Antonio Garra spent his early years

Mission Indians, as they became known, were basically servants in the parishes in which they lived. They were provided with practical and religious instruction by Catholic priests but in exchange they worked the buildings and fields for their room and board. They were also subjected to corporal punishment at the whims of the priests. They were granted their freedom by the newly independent government of Mexico in 1833 but the villages they returned to were very different from those left to them by their ancestors.

To begin with, Mexico now claimed ownership of all California land and was giving it in the form of land grants to powerful white men. In 1844, Mexico issued a grant of 45,000 acres in the heart of Cupeño territory to an American named Jonathan Warner. Warner built a farm where he raised livestock, and set up a store to serve travelers along the route from Yuma to Southern California. Among the goods and supplies he sold there was liquor for which local tribes seemed to have a decided weakness. Plied with cheap liquor and deprived of ownership of their land and purpose for their lives, local Native Americans became increasingly dissolute.

Warner-Carrillo Ranch House where John Warner lived

A notable exception was Antonio Garra. By 1850, he was chief of the Cupeño tribe. According to the San Diego Herald, Garra was “regarded by all who know him as a man of energy, determination and bravery.” By Garra’s time the Cupeños had lived in the area for more than 800 years. In their native language, the tribal name meant “people who slept here.” They traditionally lived in the mountains and foothills ranging from Warner Springs to Agua Caliente, but the arrival of the Spaniards changed all of that.

Warner Springs, San Diego

Garra lived in the community of Kupa (present day Agua Caliente) along the main road that led from Yuma west to San Diego and Los Angeles. He likely owned livestock and offered some kind of service to travelers that provided him a comfortable living. His was a large home with an extensive library and it was situated near hot springs that drew many visitors seeking relief from a variety of ailments. His letters show him to have been literate and thoughtful, and we know he was deeply troubled by the implications of so many settlers seeking homes in what had traditionally been Native American territory.

Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo had landed at Point Loma in 1542, and from there the relentless encroachment of white men took hold in San Diego. In 1769, Father Junipero Serra established a mission in Old Town, and by 1794 there were more than 1,400 Natives in residence. The San Luis Rey mission was established in 1798, but the white men brought more than seemingly endless numbers, advanced technology and the Catholic religion with them. They brought deadly diseases for which Natives had no immunity. When Serra arrived, there were an estimated 20,000 Natives from various interlocking tribes in Southern California. By 1840 their numbers had been cut in half.

Presidio Park, location of the Serra Museum

By that time there was trouble in the wind, and it would be exacerbated by the Mexican War that would result in California becoming an American territory and then a state. The opposing forces in San Diego County were the Americans and the local Mexican citizens known as Californios. Caught in between were the Native tribes whose former lands were the object of the conflict. It would mark the beginning of the saga that would end with Garra kneeling in San Diego next to his grave.

In addition to Warner and Garra, some other key players in the unfolding drama included the following:

· Juan Antonio – chief of the Cahuilla tribe.

· Colonel Phillip Cooke – American commander of a Mexican War contingent of 500 Mormon troops.

· Manuelito Cota – chief of the Pauma tribe.

· Don Jose Estudillo – Californio landowner descended from Spaniards.

· Antonio Garra, Jr. – son of the Cupeño chief.

· Agostin Haraszthy – San Diego Sheriff and tax collector.

· Jose del Carmen Lugo – son of Antonio Lugo, owner of a San Bernardino rancho

· Andres Pico – cavalry leader of Californio forces loyal to Mexico.

· Bill Marshall – an American who had become friendly with Warner and watched the ranch when Warner was away on business.

· Jose Antonio Serrano- owner of a Pauma rancho.

Location where the Battle of San Pasqual was held

The Mexican War was triggered by the annexation of Texas by the U.S. in 1845, and lasted until 1848. Most of it was fought thousands of miles from California. But there were several skirmishes in Southern California, and it was obviously difficult for the area’s tribes to understand where their allegiances should lie. To complicate matters, there were animosities between some of the tribes.

Jose Antonio Serrano’s Rancho https://www.paumatribe.com/history/rancho-era/

In December of 1846, American troops under General Stephen Kearney clashed with Andres Pico’s forces in the San Pasqual valley and they fought to an effective draw with both sides suffering significant losses. In the aftermath of the battle, eleven deserters from Pico’s force retreated to Jose Antonio Serrano’s Pauma rancho.

Nearby were two Pauma villages led by Manuelito Cota. Some believe the Natives were in a state of rage due to the killing of tribesmen by Californio troops, or alternatively that Kearney had made it known he would not object to tribes overthrowing their former masters. In either case, the prisoners were cruelly slaughtered by the Pauma tribesmen.

Jose del Carmen Lugo and Juan Antonio were deputized by the local authorities to punish the Paumas. They trapped the Natives in the Temecula valley, and with the help of Cahuilla tribesmen, killed 38 of the Paumas, and reportedly some Cupeño tribesmen too. In response to the chaos in the area, the American army detailed a 500-man unit of Mormon troops from the nearby San Luis Rey Mission to restore order.

That unit was commanded by Colonel Phillip Cooke, and he quickly sought meetings with Bill Marshall and Antonio Garra. The San Diego Herald noted that Garra had unbounded power and influence over the Natives. The meetings cooled the situation to a degree but animosities simmered.

Over the next several years, the U.S. government made many concessions to Native tribes in Northern California. They received land, cattle and supplies in exchange for their agreement to live peacefully with the Americans. All of this was managed by a federally appointed Native agent. There were no such concessions made to Southern California tribes, nor was there an Native agent to manage rising tensions between settlers and the tribes.

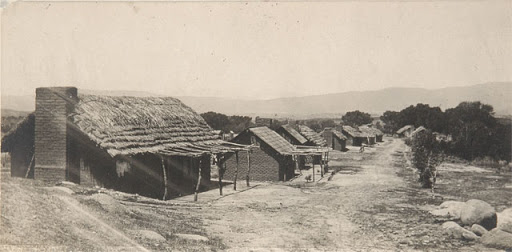

Agua Caliente tribe of Cupeño Indians

Promises of treatment similar to that given to Northern California were floated out but they never materialized for Southern California tribes. In 1850 word came that an agent was on his way to San Diego to negotiate terms with local tribes but that official never arrived. In the meantime, the Cupeños were forced to pay taxes based on the perceived value of their livestock that grazed on land the tribe no longer owned, but they had no say in their governance. The conditions that led to the American Revolution were now in place in San Diego.

As he seethed over the treatment, Garra continued to watch streams of settlers pass through Cupeño territory. He had to know that eventually his people would be badly outnumbered by settlers who would have government representation that would be denied to them. During this period, Yuma Natives rose up and killed a number of sheepherders attempting to cross the Colorado River, and one who escaped identified Antonio Garra as one of the hostiles. Garra seemed to have plans that extended beyond tribes in the immediate area.

In fact, Garra was in contact with tribes as far away as Baja California, and was attempting to organize an uprising to include all Southern California tribes. Garra made an entreaty to his old enemy, Juan Antonio of the Cahuilla tribe. Juan Antonio appeared to support Garra’s plan for expelling the Americans, and he agreed to send a messenger north to persuade the San Joaquin tribe to join the uprising.

Cahuilla tribe

In November of 1850, Garra was ready to set his plan in motion. That plan called for the Yumas to destroy San Diego, the Cahuillas and Cupeños to attack Los Angeles and the Tulare Natives to strike at Santa Barbara. In a letter to Don Estudillo, Garra assured him that the target of the attacks would only be the towns and settlements of Americans. The Californios would be left alone, and even encouraged to fight with the Natives to reclaim dominion of California.

On the night of November 21, the plan went into action. A chief of the Cahuilla tribe led an armed contingent against Warner Ranch while Garra’s son, Antonio Garra Jr., led a raid against the hot springs at Kupa where three Americans were living and using the hot springs. Garra himself later claimed to be under the weather and not present at either raid. Warner received advanced notice of the raid and moved his family to San Diego ahead of time remaining behind with two of his workers. He managed to kill two of the attackers before escaping himself. Garra Jr.’s band killed the three Americans at the springs.

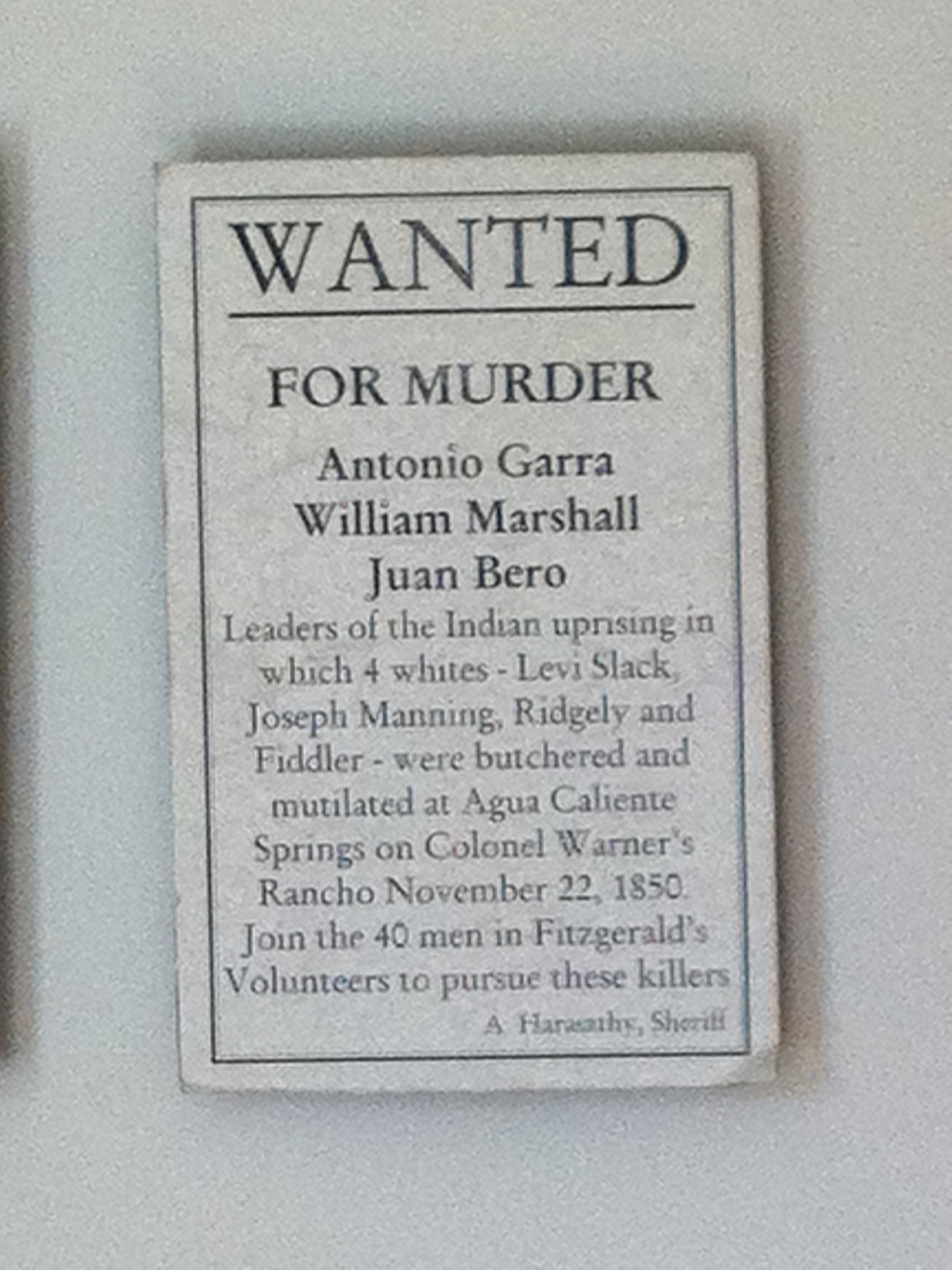

Anticipating retaliation, the Cupeño’s abandoned their village and fled to the Cahuilla village at Los Coyotes Canyon about two days ride away. Meanwhile San Diego was abuzz with news of the attack, and the San Diego Herald speculated that as many as 10,000 Natives were involved in the outbreak. Estimating that Garra alone would have 3,000 warriors within days, Sheriff Haraszthy requested reinforcements from the state government. Citizens of San Diego were in a panic, expecting an attempted massacre to come any day. In response they organized and armed themselves, posting sentries day and night.

Display with Agoston Haraszthy at Old Town’s Sheriff’s Museum

Warner returned to his ranch to find it destroyed, killing an Native he passed along the way carrying some of his property. Meanwhile Garra was consolidating his forces at Los Coyotes Canyon and putting out desperate calls for reinforcements from California tribes. In his excellent book, “When the Great Spirit Died: The Destruction of the California Indians 1850-1860,” William B. Secrest estimates that Garra never had more than 200 fighters with him, and had only a few guns to go along with bows and lances.

There were no such limitations among the Americans. Governor John McDougal put out a call for volunteers to suppress the revolt, and received 50 U.S. Army troops that that been stationed in Oregon to augment them. The earliest volunteers under Captain E.H. Fitzgerald, reached Warner Springs on December 1, and proceeded on to Kupa where they found the missing Americans dead with their hands tied behind their backs. After burying the dead, Fitzgerald ordered burning of the village, assumed to include Garra’s fine home, before moving on toward Los Coyotes Canyon.

Juan Antonio of the Cahuilla tribe found himself in a box. He did not think that Garra could succeed, and neither the Californios nor the Americans trusted him. He assumed his way out was to turn on Garra with whom he had often been in conflict anyway. It was with that in mind that Garra and Antonio arrived at a meeting with vastly different agendas. Garra expected to learn of augmented forces, but instead he was arrested by Antonio and his men, and stripped and bound. Antonio was stopped from killing Garra on the spot, and instead took him to the Cahuilla village. Upon learning of Garra’s capture his warriors dispersed and Antonio announced the war was over.

Mop up operations would be needed in order to completely put down the insurrection, and in the process, Bill Marshall and Garra’s son were among those captured. All of those Natives deemed to have taken part in killing Americans, including Antonio Garra Jr., were executed in the field.

Marshall and a Californio named Juan Verdugo were accused to be in support of the Natives, so they were taken to San Diego for trial. Marshall and Verdugo were found guilty and on December 12, 1851, they were bound and noosed while standing in a wagon. When the wagon was driven away, they slowly strangled while dangling five feet above the ground. When Garra was brought to San Diego and interrogated several weeks later, he absolved Marshall and Verdugo of any uncoerced participation in his uprising. He admitted they had participated only because he threatened to kill them if they did not. The hangman had been too quick.

Antonio Garra Wanted poster

Garra arrived shackled in San Diego on January 9, 1852. He was put on trial on January 16th, and defended unsuccessfully by an army major. The trial lasted less than two days and he was convicted on charges of treason, murder and robbery. He was executed on January 19th.

Antonio Garra was not the first Native American leader to fail in attempts to deal peacefully with the white man. The Pilgrims survived their first winter in Massachusetts only because of the kindness and support of the great Wampanoag chief Massasoit. But the patience of indigenous people did not yield fair outcomes. The great Sioux Chief Red Cloud is quoted as saying, “They made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one; they promised to take our land, and they took it.”

The Wampanoag’s friendship with the Pilgrims did not last through another generation. Massasoit’s son, King Phillip, was ambushed and murdered by a rival Native American in service of the whites. Among other great chiefs to later die in conflict with whites were Black Kettle (Cheyene), Crazy Horse (Lakota), Mangas Coloradas (Apache), Sitting Bull (Lakota), Spotted Elk (Lakota) and Tecumseh (Shawnee). Several of these great leaders were killed while in the “protective custody” of American authorities.

Crazy Horse of the Lakota tribe

Native American leaders had two choices when dealing with white men encroaching on their territory. Either they could capitulate in which case they would lose their land, or they could resist in which case they would lose their land and their lives. They can be excused for believing they had little to lose.

So why do we remember Antonio Garra in San Diego today? He unquestionably killed people and plotted to kill many more. And he clearly failed to achieve his goal of pushing the whites out of California.

But we remember him because he was unquestionably brave, because we are obligated to also view events through the eyes of Native Americans, and because history favors resistors. We remember appeasers but we don’t honor them. There are no statues in the world to Neville Chamberlain, but there are many to Winston Churchill. There is no Juan Antonio Day in San Diego, but there is an Antonio Garra Day.

As many as 18 million Natives were living in what is now the United States in 1492 when Columbus arrived in present day Bahamas. By 1800 their numbers had declined to 600,000, and in the next century it dropped again by more than one-half. Much of that decline can be attributed to diseases for which Native Americans had no immunity, but much of the rest results from the fact that our government treated them as less than human.

Our government treated defeated Natives much more brutally than it did whites who transgressed in far worse ways. Abraham Lincoln signed a single Confederate death order in the aftermath of the Civil War in which 400,000 Union soldiers were directly or indirectly killed by Confederates. In contrast, he signed death warrants of 38 Dakota warriors who were hanged for killing fewer than 500 whites in an uprising in August of 1862. Those warriors went to their deaths dancing on the gallows and calling out their names lest they be forgotten by their tribe.

El Campo Santo Cemetery where Antonio Garra is buried

Antonio Garra died with the same resolution and bravery as those Dakota warriors. The events he had lived through appeared to leave him unafraid of death. He had seen the white man take Cupeño land while giving nothing in return. The grant that gave much of their land to Warner had termed it “vacant and abandoned” as if the Cupeño tribesmen who had been there for hundreds of generations were merely apparitions.

After Garra’s death his tribe lived in buildings abandoned from mission days. In 1893 the land became the legal property of John G. Downey, and he sued for the removal of Native “interlopers.” They were moved to a small reservation at the Luiseño village of Pala in 1903. After first sleeping in the open due to lack of housing, the Cupeños slowly made Pala their home as it remains today.

So why should we note and remember the life of Antonio Garra in San Diego? He was clearly a resolute and brave person, and his actions seemed intended to insure the survival of his people and their culture. But beyond that, his tale is an allegory for the experience of American Natives as a whole. Even in those cases where Native Americans attempted to cooperate and co-exist with whites, they were steamrolled into oblivion, often brutally.

We cannot celebrate the national experience without coming to honest terms with the treatment of the indigenous people who have lived here for centuries. And in that vein, we should celebrate the life of Antonio Garra.